Paul Smith, Impressionism Beneath the Surface (New York : H.N. Abrams, 1995)

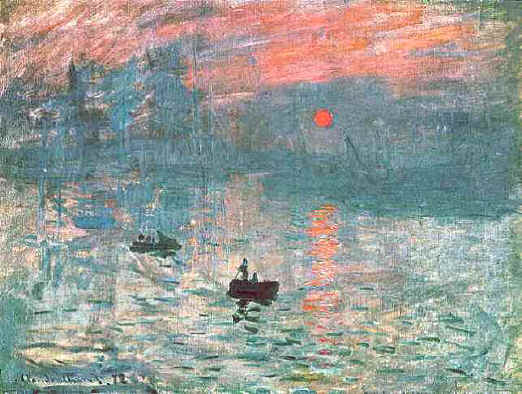

In April 1874, Claude Monet showed Impression, Sunrise (1873) at an exhibition by a group calling itself "Painters, Sculptors, Engravers etc. Inc." This was the first of what we now know as the Impressionist exhibitions. Monet's painting and its eccentric title helped give Impressionism its name and, indeed, for many people, have come to exemplify Impressionism in general. The critic and friend of the Impressionists, Theodore Duret, wrote in 1878:

"If the word Impressionist was... accepted to designate a group of painters, it is certainly the peculiar qualities of Claude Monet's paintings which first suggested it. Monet is the Impressionist painter par excellence." Duret then went on to give his reasons:

Claude Monet has succeeded in setting down the fleeting impression which his predecessors had neglected or considered impossible to render with the brush.... No longer painting merely the immobile and permanent aspect of a landscape, but also the fleeting appearances which the accidents of atmosphere present to him, Monet transmits a singularly lively and striking sensation of the observed scene. His canvases really do communicate impressions.

Claude Monet, Impression, Sunrise (1873)

Edouard Manet, Music in the Tuileries (1862)

Duret was arguing that what made a painter an Impressionist was that he or she pursued transient atmospheric effects, which he seems to suggest were also the painter's impressions. However, Duret's definition of Impressionism, and the idea deriving from it that Monet was the archetypal Impressionist, are not without their problems. For one thing, as we shall see, an impression was not just the record of transient effects of light and atmosphere. For another, the Impressionists were a group whose members' work was far more diverse than Duret suggests.

This, of course, raises the questions who and what were the Impressionists? One familiar answer is that they were a group of painters, some of whom first met between 1860 and 1862 at an informal studio, the Academie Suisse, and the rest of whom shared time together between 1862 and 1864 in the studio of the painter Charles Gleyre at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts. Monet, Camille Pissarro, and Paul Cezanne (who met at the Academie Suisse) and Auguste Renoir, Alfred Sisley, and Frederic Bazille (who met Monet at Gleyre's) are said to have united in opposition to a conservative, classical training and, under the example of the landscapists Eugene Boudin and Johan Barthold Jongkind, went to paint nature in the open air in a novel, bold, and "sketchy" manner.

The Impressionists were indeed dissatisfied with the classical training given at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, or the state-run school of fine art, and especially with its emphasis on historical and mythological subject matter and "correct" drawing in the manner of the antique or Renaissance masters such as Raphael. Examples of such work are Alexandre Cabanel's, The Birth of Venus (c. 1863) and Gleyre's Minerva and the Graces (1866). Their dissatisfaction was not just with the esthetic standards of the Ecole, but with the fact that it was governed by an institutional structure which maintained these standards, to which artists had to subscribe in order to be successful. The Ecole was governed by the Academie des Beaux-Arts, itself governed by the Institut de France. The professors at the Ecole were chosen from among the members of the Academie, and the same body dominated the jury which awarded prizes at the annual Salon, or state-sponsored exhibition, where an artist could hope to gain critical recognition or official patronage. (At the Salon of 1863, Cabanel's Venus was awarded a gold medal, which indicates the prevailing attitudes.) However, many young artists of the period opposed the Ecole and its stranglehold on art. Moreover, all the Impressionists mentioned so far had work accepted at the Salon in the 1860s, Monet, Renoir, and Pissarro even enjoying some success with theirs. One reason for this was that the Salon was not entirely dominated by classicism. It had been "liberalised" as a propaganda manoeuvre by the autocratic Emperor Napoleon III and even if landscape and genre scenes did not enjoy the same institutional prestige as history and mythology, they were none the less exhibited and given serious attention by critics and the public.

.jpg)

Alfred Sisley, Flood at Port-Marly (1876)